Moving to New York was like some predetermined departure from the California dream.

However many flights I took from New York, to New York, I felt that many pieces had been scattered upon my leaving -- pieces of the pink princess umbrella I would hold high over my head, ruining my tap shoes in the rain, running foolishly from my brother as he pretended to be a Scooby Doo villain we’d just seen on TV; pieces of myself that had walked onto unfamiliar stages holding microphones or the red velvet of wings; pieces of photographs that I left waiting to be strung over my East Village apartment walls; pieces of clothing that wouldn’t make it into my last suitcase out of the city.

I think those pieces speak of flights I took that were in a sense flightless, the clouds above the midwestern states just pink cotton figments of some thing, some place that wasn’t really going anywhere. These moments in the air somehow became runways, each with a distinct ecology, as if the act of traveling zeroed in on this inescapable land of emotions.

On my way to New York, I was taking Homestead Valley with me, the Pixie Forest, the Weedon Redwoods -- in which a hiker recently discovered a pack of active explosives set by some 60s rebel group. The other night when my family sat awaiting the next tweet from the sheriff’s department, a few blocks from the trees that could potentially catch fire in an explosion, I thought of how unbelievable it was that in that moment we feared a bomb more than a pandemic. I thought of those times my dad and I would take that same 6a trailhead where the ammunition was found, up to four corners where one road led to the ocean, another to San Francisco, another to the mountain, and the last back to my home. We’d celebrate over a can of lemon San Pellegrino and dixie cups; on one side of our selfie, the valley, where our house lay tucked inside the eucalyptus, and then behind our camera, the Pacific. But we never achieved capturing all four corners in the selfie, no matter how upside down our faces or strained our backs, it was only ever two compass directions we managed. And growing up, it was rare to venture down more than one of those roads in one trip, yet on some ambitious days we made it, like that impossible selfie.

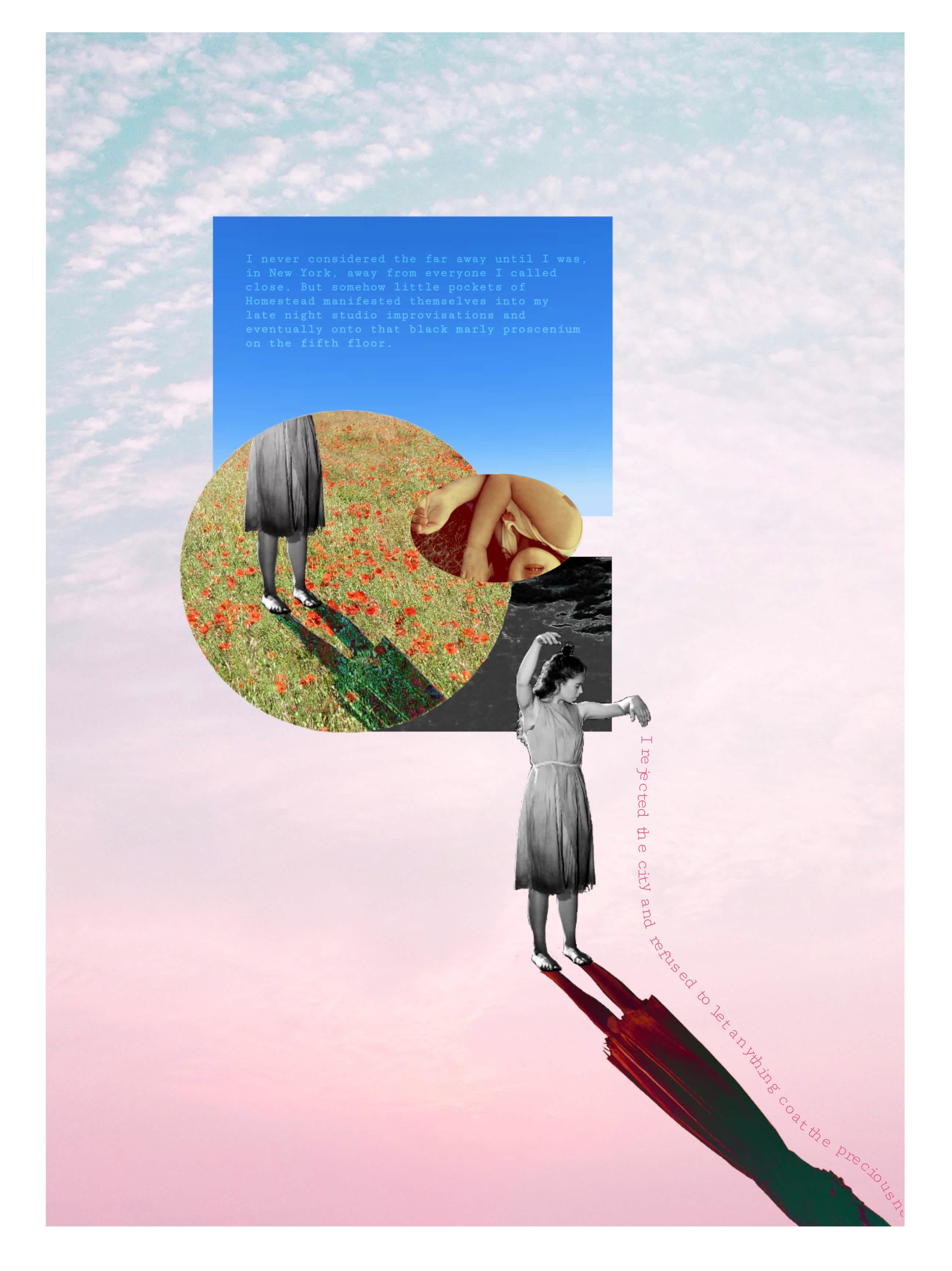

I never considered the far away until I was, in New York, away from everyone I called close. But somehow little pockets of Homestead manifested themselves into my late night studio improvisations and eventually onto that black marley proscenium on the fifth floor.

In isolation there are many things that surface, like the deep orange pulp from the juice you just squeezed, or the oil separating from the egg in the pancake mix you thought you mixed thoroughly. On Mother’s Day, one of the first I would spend here in California since moving to New York, I softly perused kodaks from the not-so-long-ago years of the disposable camera. Our small black Nikon traveled north with us to Bodega Bay and Mendocino, south to Monterey and Cambria, east to Squaw Valley and Yosemite National Park, clicking under the pressure of my dad’s worn fingers and his directives to pull tighter into the frame. These photographs are organized by month into wallet-sized pockets; I wondered how in such a swift number of years, we had transitioned from filing cabinets to portable tablets in our pockets carrying the table-side french fries, and the pumpkin patch maze, and the first snow men, and the birthday parties, and the preschool graduations. But skating their glossy edges with my clammy hands that morning confirmed I could wander back into those haystacks and the forests surrounding my backyard at any time, regardless of whether the portraits remained physical or had swooped into our now endless digital libraries.

I went to New York full of laminated 4 x 6 album pages, but often slid through my time there photoless. I didn’t want to believe being in this transitory adult state was transferable or valuable enough to record, because for many months I rejected the city and refused to let anything coat the preciousness of the past. Who was I without my brother -- who now attends college on the west coast -- and the ridiculous games we’d invent to pass the summers in the same garden from which today I write. Who was I without those magical places where snow fell like crystal dust and waves crashed to and fro, forgetting they washed the shore the moment they retreated.

I remember walking home pressing down what had occurred that day, as if it couldn’t ever live up to the sweet, saturated light in those photographs. I regret those days very much, as if I favored this dissociated state of memory over just letting memory arise when I most needed it. It made me turn away from the best people, the best experiences, because I couldn’t let go of some expired idea of my imagination.

Luckily I moved on from that. I think I learned to inhabit the residue that these places left inside me -- a wistfulness that existed between the trees -- and transfer it incrementally into the studio, into the newsroom, into the streets between 2nd Ave and East River Park where I’d clear my head and pretend New York was just a place I walked to access the California I knew and loved.

But by my last few months there, New York I could also say I knew and loved -- when I’d read a book past all the East Side playgrounds and vibrant cafés to ease off the Sunday morning caffeine, when I’d blast music past Tompkins Sq in the early hours heading back from a dinner that thankfully went way too long, when I’d sit a little buzzed with my roommate and predict if I’d ever have to make a marriage pact. None of this would have happened if I hadn’t let New York in.

So in the next flight east, I’ll rest, confirming these places haven’t gone nor are going anywhere out of the reach of my hand in our dusty photo drawer or in the misty spaces of what I still remember. For some, there are straits in the neural-networks that connect the memory of places with their geographical origins. For others, the heart connects place to memory. For now, I’m one of the latter.